- About

- Consultation

- Programs

- Resources

- News & Events

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

For the second year in a row, Dartmouth is ranked number one for “Commitment to Undergraduate Teaching” by U.S. News & World Report. The ranking, which was released in August, is based on the nominations of college presidents, provosts, and admissions deans and reflects the College’s reputation among its peers.

But what does a number one ranking really mean? Dean of the Faculty Michael Mastanduno says, “We must be careful in placing too much weight on rankings, but I do think they can indicate something meaningful. Many schools that emphasize a commitment to both teaching and research are really just looking for top scholars and aren’t so worried about teaching. Other schools look to hire great teachers but do not have a high scholarly expectation. When we hire, we’re looking for outstanding scholars who are dedicated teachers and willing to work closely with undergraduates. The ranking reflects that we’re one of the top schools to place such a heavy emphasis on that intersection.”

Associate Professor of Sociology Kathryn Lively (left) meets with Blythe George ’12 during office hours. Dartmouth’s 8-to-1 student-to-faculty ratio enables close contact with professors. (photo by Joseph Mehling ’69)

Dartmouth’s reputation for teaching not only attracts faculty interested in working with undergraduates, but students who actively push professors to be accessible. As Kathryn Lively, an associate professor of sociology who sits on the advisory board of the Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning (DCAL), puts it, “The students have such high expectations about teaching that in some ways they pull the faculty along.”

But reputation and self-selection, say faculty, don’t tell the full story of what happens in Dartmouth classrooms, labs, and independent studies. So how does Dartmouth define great teaching? How do faculty assess their own performance? What measures show what Dartmouth is doing right—and where it needs to improve?

What the data show—and don’t show

The most accessible data points to cite in assessing Dartmouth’s teaching advantages are student-to-faculty ratio and class size. At Dartmouth, there are currently eight students for every professor. In 2009–10, 63 percent of classes enrolled 19 students or fewer, while only 8 percent enrolled 50 or more. Students enrolled in approximately 1,000 independent studies working one-on-one with faculty. Additionally, 230 undergraduates aided faculty research or conducted independent research as Presidential Scholars or Senior Fellows. In their first year at Dartmouth, students must take at least two seminar-style, writing-intensive courses. And in recent surveys of graduating seniors, 98 percent have reported being “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the quality of the academic experience.

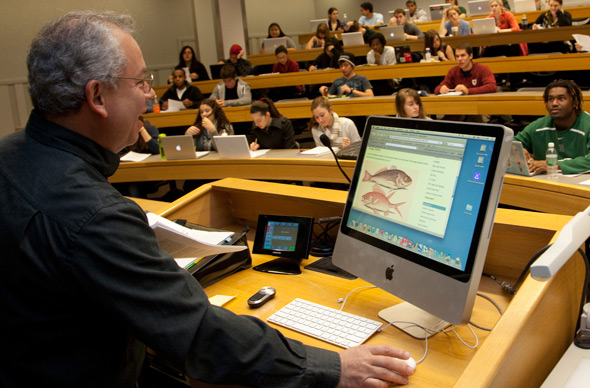

N. Bruce Duthu ’80, the Samson Occom Professor and chair of Native American studies, teaches his course “Indian Country Today” using “smart classroom” technology in Carson Hall. (photo by Joseph Mehling ’69)

These data indicate that Dartmouth students have ample opportunity to work closely with faculty. But according to Tom Luxon, the Cheheyl Professor and director of DCAL, “Just being accessible is not a guarantee that learning is happening. It’s good, but not sufficient.”

Models of teaching: from delivery to production

“I don’t think there’s a single definition of great teaching at Dartmouth,” says Mastanduno. “We go out of our way to think about the multiplicity of ways someone could contribute as a teacher. It would be wrong to think that to teach at Dartmouth you must be a great lecturer in a large auditorium. We also appreciate the teacher who works one-on-one or in small groups with students, who gets students excited in a smaller setting.”

Luxon goes further, arguing that a historical model of the “inspiring, dazzling lecturer” is changing. While good lecturers do motivate, he points to current research showing that students learn best as active participants in their own learning and argues that modern technology gives students tools that were beyond the reach of previous generations. “A student in a classroom today with a laptop has access to the catalogs of every library in the world,” he says. “It’s time we as scholars start teaching our students how we do our work, because we can.”

A key component of DCAL’s mission, he says, is “to help shift the culture of higher education from one that regards its mission as delivery of instruction to one that sees its task as producing learning.”

What Luxon calls the production model of learning is at work in Lively’s “Sociological Imagination” course, where students apply the lens of sociology to their personal histories, and in Assistant Professor Craig Sutton’s “Linear Algebra” class, where his goal is for students to “see math as a creative, artistic endeavor” beyond problem sets and grades. “In office hours, we talk and talk until they get it—or until I pass out,” he says.

Assistant Professor of Mathematics Craig Sutton (right) works with Caleb Cook ’11. Sutton’s goal is for students to “see math as a creative, artistic endeavor” beyond problem sets and grades. (photo by Joseph Mehling ’69)

Even academic architecture is changing to reflect new models. Luxon cites the example of the Class of 1978 Life Sciences Center, slated to open next fall, which features 30- and 80-seat “smart classrooms” with whiteboards and displays for small group work.

Evaluating and improving faculty performance

DCAL was established in 2004 with major gifts from Gordon Russell ’55 and R. Stephen Cheheyl ’67 to provide a place where faculty of all levels can go to share pedagogical insights and develop professionally as teachers. According to Mastanduno, DCAL is distinctive in academia for its emphasis on career-long professional development, rather than focusing more narrowly on training novice teachers.

“Even the best teachers go to DCAL because everybody can always be better,” he says. “You’d be surprised that sometimes even simple things can help you be more effective in the classroom. It’s an important resource.”

Even with DCAL, outside of the reviews that help determine promotion and tenure, peer mentoring among faculty colleagues is rare. “Peer evaluations would really benefit us, myself included,” says Lively. Interestingly, says Sutton, faculty have no compunction about attending each other’s research talks, but treat the classroom as a private sphere.

Luxon acknowledges the challenge. “The notion of the classroom as a private space and a syllabus as private intellectual property is not helpful. We want people to think of their classrooms as open spaces. The more we share, the better.”

In recent years, Dartmouth has instituted a standard, campus-wide course evaluation for students to complete after each term. “These tell you a great deal about what students feel that they’re getting out of courses,” says Mastanduno. “They tend to be very thoughtful, not just in terms of ‘I liked this’ or ‘I didn’t like that,’ but ‘these are the ways this can be improved.’”

Dartmouth weighs student evaluations heavily in the tenure review process. According to Mastanduno, “We’ll write to roughly eighty former students in a tenure process, hoping to receive about twenty letters. These letters tend to be detailed and reflective and give you a good idea of the kind of impact the professor had on them as a young person.”

How should Dartmouth measure teaching outcomes?

One challenge of measuring good teaching is that many classroom goals are intangible. Says Sutton, “The best classes are the ones where everyone in the room knows something cool happened, even if we can’t articulate what. Yes, we had fun; yes, we were challenged; yes, we were actively engaged in the process—but it’s greater than the sum of those parts.”

Still, President Jim Yong Kim has asked the faculty to imagine how they could get at that sum, drawing an analogy to measuring complex outcomes in medicine. “In other impossible-to-measure areas we’ve made great progress in the past thirty years. I’d love to see higher education moving in that direction,” he says.

An important step, says Luxon, would be for academic departments to develop clear learning assessments. A model is currently underway at the Institute of Writing and Rhetoric, which is conducting a program-wide assessment of the teaching of writing. DCAL has foundation funds to recruit two more departments to conduct similar analyses for their majors, and then “work backward from there to design assessment structures for students that tell us if they’re achieving these outcomes.”

Says Mastanduno, “Establishing metrics is a great challenge that I don’t think has been met decisively well anywhere. President Kim wants to be on the frontier. Do I know what the answer is? No. But there are a lot of people here who are excited to help figure it out.”