Davis, Barbara Gross. Tools for Teaching. Vol. 1st ed, Jossey-Bass, 1993. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,url,uid&db=nlebk&AN=26088&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Feichtner, S. B., and E. A. Davis. "Why Some Groups Fail: A Survey of Students' Experiences with Learning Groups." Journal of Management Education, vol. 9, no. 4, Nov. 1984, pp. 58–73. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/105256298400900409.

Felder, Richard M., and Rebecca Brent. "Navigating the Bumpy Road to Student-Centered Instruction." College Teaching, vol. 44, no. 2, Apr. 1996, pp. 43–47. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1080/87567555.1996.9933425.

Felder, Richard M., and Rebecca Brent. "Cooperative Learning." Active Learning, edited by Patricia Ann Mabrouk, vol. 970, American Chemical Society, 2007, pp. 34–53. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1021/bk-2007-0970.ch004.

Fournier, Eric. "Using Roles in Group Work." Washington University in St. Louis Center for Teaching and Learning, https://ctl.wustl.edu/resources/using-roles-in-group-work/. Accessed 2 Feb. 2021.

Freeman, Lynne, and Luke Greenacre. "An Examination of Socially Destructive Behaviors in Group Work." Journal of Marketing Education - J Market Educ, vol. 33, Apr. 2011, pp. 5–17. ResearchGate, doi:10.1177/0273475310389150.

Gaunt, Helena, and Danielle Shannon Treacy. "Ensemble Practices in the Arts: A Reflective Matrix to Enhance Team Work and Collaborative Learning in Higher Education." Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, vol. 19, no. 4, SAGE Publications, Oct. 2020, pp. 419–44. SAGE Journals, doi:10.1177/1474022219885791.

Hassanien, Ahmed. "Student Experience of Group Work and Group Assessment in Higher Education." Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, vol. 6, no. 1, July 2006, pp. 17–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1300/J172v06n01_02.

Heller, Patricia, and Mark Hollabaugh. "Teaching Problem Solving through Cooperative Grouping. Part 2: Designing Problems and Structuring Groups." American Journal of Physics, vol. 60, no. 7, American Association of Physics Teachers, July 1992, pp. 637–44. aapt.scitation.org (Atypon), doi:10.1119/1.17118.

Monson, Renee. "Groups That Work: Student Achievement in Group Research Projects and Effects on Individual Learning." Teaching Sociology, vol. 45, no. 3, SAGE Publications Inc, July 2017, pp. 240–51. SAGE Journals, doi:10.1177/0092055X17697772.

Oakley, Barbara, et al. "Turning Student Groups into Effective Teams." Journal of Student Centered Learning, vol. 2, no. 1, 2004, pp. 9-34. https://www.engr.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/drive/1ofGhdOciEwloA2zofffqkr7jG3SeKRq3/2004-Oakley-paper(JSCL).pdf

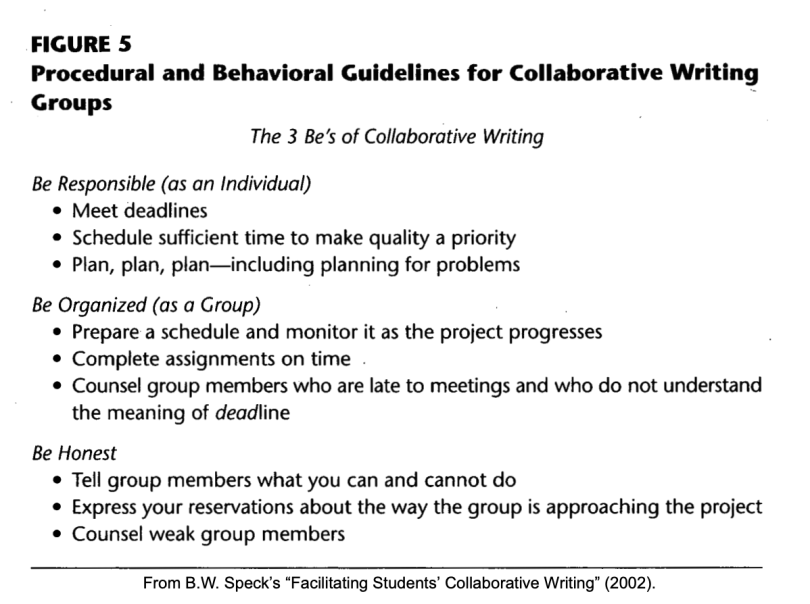

Speck, Bruce W. Facilitating Students' Collaborative Writing. Jossey-Bass, 2002, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/ERIC-ED466716/pdf/ERIC-ED466716.pdf, Accessed 2 Feb 2021

Wenzel, Thomas J. "Evaluation Tools To Guide Students' Peer-Assessment and Self-Assessment in Group Activities for the Lab and Classroom." Journal of Chemical Education, vol. 84, no. 1, 2007, p. 182.

Wildman, Jessica, et al. "Student Teamwork During COVID-19: Challenges, Changes, and Consequences." Small Group Research, vol. 0, no. 0, 2021, pp. 1–16.

Wilson, KJ, et al. "Evidence Based Teaching Guide: Group Work." CBE Life Science Education, http://lse.ascb.org/evidence-based-teaching-guides/group-work/. Accessed 2 Feb. 2021.